(Read the first installment of this series here.)

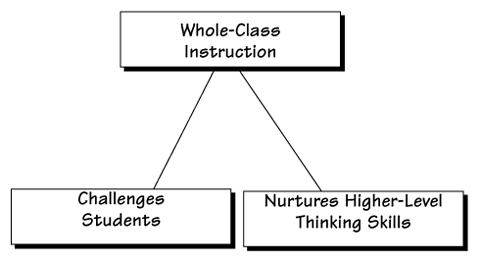

This week we are continuing our series of examining literary elements as you teach novels in your classroom. The article below describes an approach to using an important scene. Use the ideas to create classroom activities or to engage your students in whole-class or small-group discussions.

An Important Scene

Overview: Novels are divided into chapters, but the building blocks of fiction are scenes. A scene usually has a clear beginning and ending, though its seeds often are planted in earlier scenes and its tendrils extend into later scenes. Scenes can revolve around major events, minor events, character interactions, internal monologues, or just about anything else.

The Basic Questions:

- What are the 5 Ws (who, what, when, where, and why) of the scene?

- In what ways is this scene caused by or foreshadowed in an earlier scene?

- In what ways does this scene cause or foreshadow a later scene?

The Big Question:

Why is this scene important to the novel as a whole? Students should consider how this scene establishes or contributes to such literary elements as characterization, point of view, setting, genre, and theme.

Dig Deeper:

- What is the mood of the scene? How do the author’s word choices and sentence structures add to or create this effect?

- How could this scene have ended differently, and what effect would that different ending have had on the scenes that follow?

Get Graphic:

Have students create a combination storyboard/flow chart of the scene by drawing 4–6 images from the scene and showing how each image leads to the next.

Students should then explain how the author’s word choices or use of imagery help the reader create mental pictures of this scene’s individual moments.

Make a Connection:

One type of important scene in a novel is when a character experiences a turning point. It is at this point that a decisive change occurs that dramatically affects the rest of the novel’s plot. Ask students to name their turning points as they read the novel. At what point did they decide that they were going to either really like or really dislike the novel? What led to this turning point?

Next week: Part 3—Sequence and Structure